The platform to London is the standard Saturday Cotswolds crowd.

Stout men in cricket club gilets with their teenage sons, also wearing gilets.

A chic femme d’un certain âge in ankle-length mink coat and leopard print ballet pumps, clutching a Louis Vuitton carrier.

A guy with a nose ring and neck tats, drinking a can of cider, complaining to his missus about his teenage sons.

“My music is like the Sound of Music compared to what they listen to.” Said around a swig of Bulmers.

There’s a kerfuffle. A line of people held up behind a pregnant woman.

She politely, and in a British “I’m-sorry-there-must-be-some-mistake” kind of way, pointed out that someone—a white middle-aged male someone—was in her seat.

He didn’t move. Put on his glasses, asked to see her ticket.

Only when it was established beyond a shadow of a doubt to the entire carriage that he was definitely in her seat did he grudgingly shift to a seat opposite me.

After a minute, I realised he was staring at me with frank hostility.

“You’re in my friend’s seat.”

“Sorry, what?” I was confused. There was no sign of a friend.

An embarrassed friend piped up from behind me.

“No, it’s ok, no worries.”

Well, let me tell you, I hopped up like that seat was on goddamn fire.

Pierced chap told me he was getting off at the next stop, so I was able to sit down again in his seat pretty much straight away.

Along came a couple, towing much luggage. They barely looked at the chap with glasses as they thrust their tickets at him.

“You’re in our seat.”

He got up grumbling and had to stand the whole dang way from Oxford to Paddington.

Perfect outward composure. In my head, Nelson from The Simpsons. Ha. Ha.

Behind me, a man down for the day from the Welsh borders described to a Canadian woman how their community was trying to hold accountable the chicken farmers that polluted the Wye river catchment area.

I’ve been there recently. The valley walls are laced with shit, fathoms deep. You can’t get near the river. It’s a shit-mire; a veritable swamp of sewage.

“It’s a long drawn out process,” he told her. “Well, anything involving lawyers is, isn’t it.” This wasn’t a question. “Only the lawyers make the money.”

She told him Canada has lots of polluted rivers too. It’s 40% woodland, she discoursed, and has lots of plains.

“For grain?”

“No, maize.”

I thought of cornfields across Manitoba, a nuclear waste of frozen husks in winter.

Trundling into West London, the new blocks of flats are west-lit plate-glass.

Balconies overlook rail lines: a view like Auschwitz. If you can watch whatever you want on a screen, who cares what’s outside your window?

Everyone searching for the best, most comfortable view of mayhem.

In the Paddington concourse, more people than I encounter in a month.

It’s overwhelming how different they all are but still so … London. London is like a carpet, or an outfit. It smothers. The fibres stick to you, embed themselves, and after awhile you are more London than anything else.

All these frictionless people passing over and through each other like water, slipping soundlessly into trains and off, through barriers and up escalators, staring at their phones.

Do you remember when tech was still textural? Chunky phones that whirred and clicked and beeped. Now the aim is frictionless: friction is failure.

Me? I like a little friction, a reassuring judder.

The bus in London vibrates like an orgasm in my shoulders. It’s really very pleasing.

I stopped at my favourite ramen spot. There was a queue but they seated me immediately at a lonesome sole perch because there was only one of me.

An unimpressed woman in the queue gave me daggers, which I had no choice but to return.

You can do nothing but insult people who are determined to be offended.

When I tried to buy wine at a wine shop, there was a bell for security. It rang and rang but the door didn’t open.

Inside, crowds of people chatted with the staff, browsed the shelves and merrily purchased wine without issue. Pressing nose to the glass, I tried to catch someone’s eye. Anyone?

Nothing.

I pinched myself to make sure I’m real—still here!—and carried on.

London seems all gyms and shiny surfaces.

You have to squint to see past, between them.

Like Lincoln’s Inn Fields where, since reading Bleak House, I can’t wander without picturing Tulkinghorn’s dimly-lit marble-filled corridors.

Today I felt a bit like the mad old bag waiting for the Jarndyce verdict. Release the birds! Lead me away to the attic.

A muffled scream from the LSE halls: somebody writing their dissertation hit a wall.

So many old houses of forgotten men. Dr Johnson, on the left. No time to join the crowds for Sir John Soane’s house—next time, Sir John!—I’ve a gathering to attend.

Still no wine for it though.

The Last Judgment pub off Chancery Lane looks inviting but no time, no time.

Pallas Athena! Ye olde Cock Tavern!

The sun is threatening to peak out. London seems a brighter, more blue-skies country than Oxfordshire. Imagine then how grey and flat is the Oxfordshire countryside.

A sign on a construction site announced “History is a work in progress”.

History is a work in progress? No, it’s not. That’s just a bald justification for your shoddy conservation efforts.

History is the past. That is its defining characteristic.

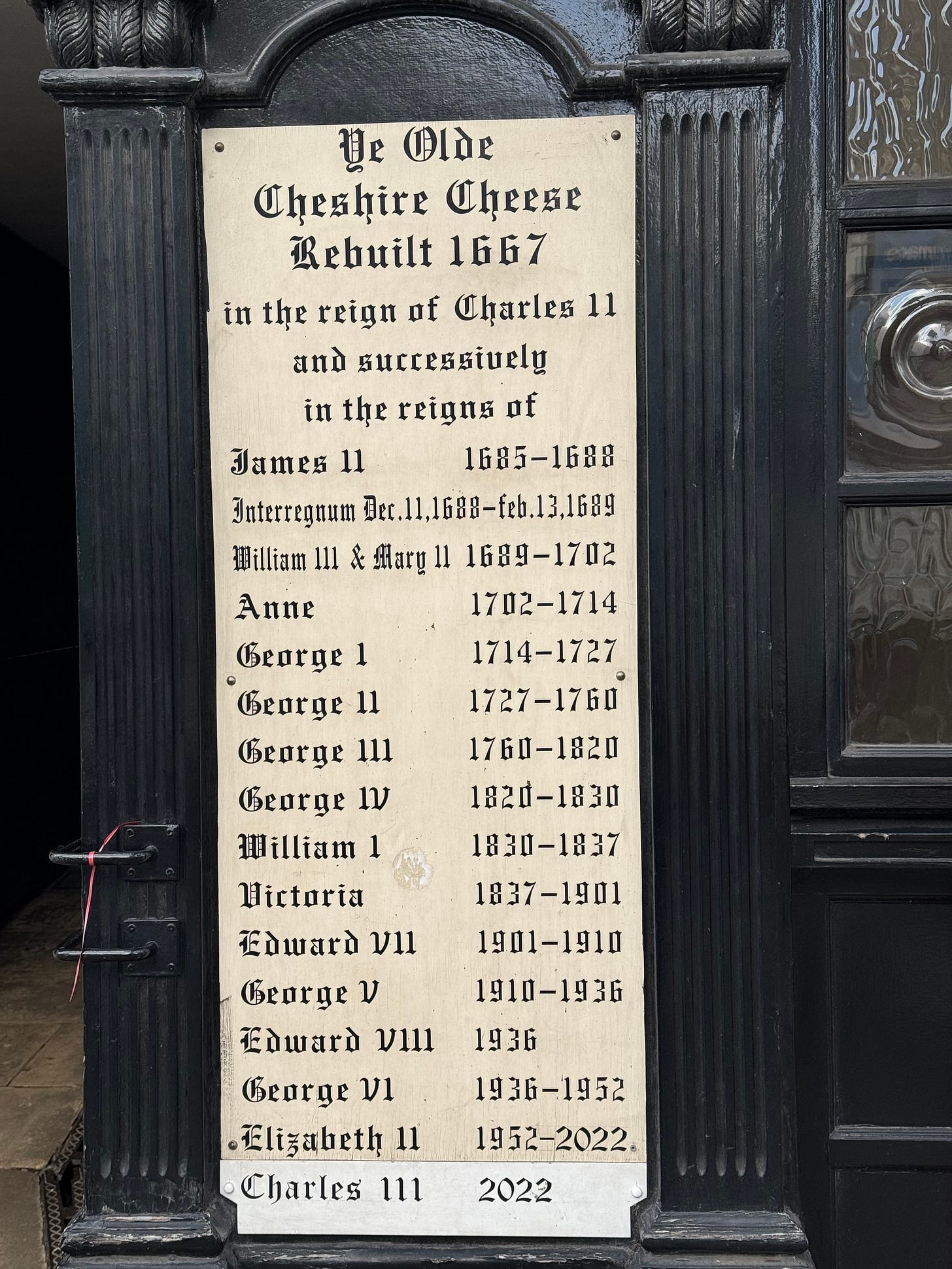

I congratulated myself on my cleverness but the Chester Cheese pub, with its newly-updated list of monarchs during its tenure, immediately reminded me this isn’t true. It’s all a work in progress.

A group of paparazzi brush past, cartoons of themselves with tripods and lenses.

I turned the tables and snapped them when they weren’t looking.

Invisible people-watching is one of my greatest pleasures.

At a crowded, but not too crowded, bar in Shoreditch before the hour of dinner later, with glass of red, perched between small tables, I was neither seen nor could I quite overhear.

Conversations smattered about me without leaving a trace. The music was indeterminate but bouncy, rhythmic.

There was a man, an unappealing man, waiting at the bar and casting little glances sideways about. The woman he was waiting for, an unappealing woman, arrived and they chatted uneasily for a moment.

After a moment, they were buoyant. Much eye contact suggested they will both be naked later. I felt happy for them.

Unlike the couple at the next table. They hate each other. Or rather, she hates him.

Fastidious in a white jumper, she is determined to be displeased, casts him venomous looks that ask why they are here in this shithole bar that is neither impressive nor exclusive nor expensive.

On the way home later, after dinner with friends, back in Paddington, I didn’t want to rub elbows while I waited for the last train, wanted to find somewhere I could sit alone.

Not an easy task in central London, let alone on Saturday evening in a mainline rail station, but eventually I found it: a magical bench on its own in a very quiet corner.

There was no one around. How was this possible? Not a single human for 100 feet in any direction. I realised I was probably the only person in central London experiencing this level of isolation right now.

A Japanese man cast a furtive glance around and sat on his own lonely bench on the other side of this abandoned concourse.

A preoccupied-looking chap passed me silently going the other way on the escalator, shoulders hunched and fists jammed in pockets.

A tiny, older gentleman, bowlegged and flat-capped, with something of the air of country Ireland about him, scurried past, eyes down.

Sometimes I look at people alone and wonder if they’re real, try to check if they cast a shadow.

I wonder if other people look at me and do the same: that woman over there frantically thumbing her phone, with a battered take out bag of noodles. Is she deranged? Is she a ghost?

Mostly they probably don’t see me at all.

Mostly, I pass through London and cast no shadow.

Which is better than the alternative.

At dinner, the waitress at the Italian restaurant sounded Italian so I asked her are you really Italian or is it just for the restaurant and she laughed and said no, really Italian, from a small village in the mountains near Milan and I said, how lovely, that’s where I want to live and she said I prefer London because it’s awake twenty four hours, not like Milan.

“In Milan, everything is closed and there are no people around when you need to go home, so it’s scary.” She paused. “As a woman, it’s scary,” she said again, as if I might have missed the point. “Trying to go home alone is hard if you work in hospitality in Milan.”

She went to get our drinks and I thought: trying to be left alone is hard, hospitality, Milan or otherwise.

Don’t you know what it’s like, navigating this world in fear.

Don’t you know what it’s like when, on a late night train, even a crowded train, the toilet floods and there’s a flock of drunk men at the door laughing and, when you look over in good humour to see what the commotion is about, some man takes umbrage at you for being too pretty or too curious or having too much personality or presence or whatever and says “she’s giving me evils” as if you and he have some intricate, interpersonal beef and you have to look away and pretend you have no ears because drunk angry men can turn violent in a heartbeat and don’t you know it, so you say nothing and hope his attention gets drawn to someone else and it does, one of his companions, a very drunk girl, who at one point threatens to vomit and he jokes yeah over there (pointing at you) fuck off, and your ears burn but you keep knitting because you got your knitting out to be unthreatening and grandmotherly but also because knitting needles are sharp as fuck and if you come near me, motherfucker, I’m putting one of them in your eyeball.

“Fuck you. Lick my asshole,” mutters the drunk girl, whose head is drowsing on his shoulder.

He helps her up and off the train. “Well, if you’re offering. I mean, I’d give it a go.”

We’re all just drowning in ourselves.

If an essay is an attempt to bail out a sinking ship, these words are a bucket of floodwater, slopped overboard.

Heave ho.

you say so much with so little

the first 3 couplets are precious

i've been to london twice / i've had the pleasure of being a yankee at a pub in twickenham / this was long ago in the eighties / i have no idea what it's like now

well now i do

hilarious

lot's of words to look up

brilliant and dire

Wow, the things you notice when you don't have your nose glued to your phone. Brava, Jill - you are welcome to give us more of these closely observed forays. ⭐