Steinbeck, ant fungus and the Zombie apocalypse

On why we play video games and read books.

Are you a gamer?

Full disclosure: I’m not and never have been.

Aside from a brief phase of being obsessed with an idiotic jumping coyote game called Crash Bandicoot when I was 15 (in which obsession I was apparently not alone), gaming has always left me with a deeply unsatisfied feeling.

You know the one. It’s the same feeling you get from clickbait or scrolling social media. The next thing will be something good, no, the next, no, the next, keep going.

Etc, ad infinitum.

As a kid, I encountered it in Inspector Gadget and Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtle cartoons (The bad guy always gets away at the end! There’s never any satisfying resolution!) or those awful Choose Your Own Adventure books that took you round and round in unsatisfying circles and never seemed to go anywhere.

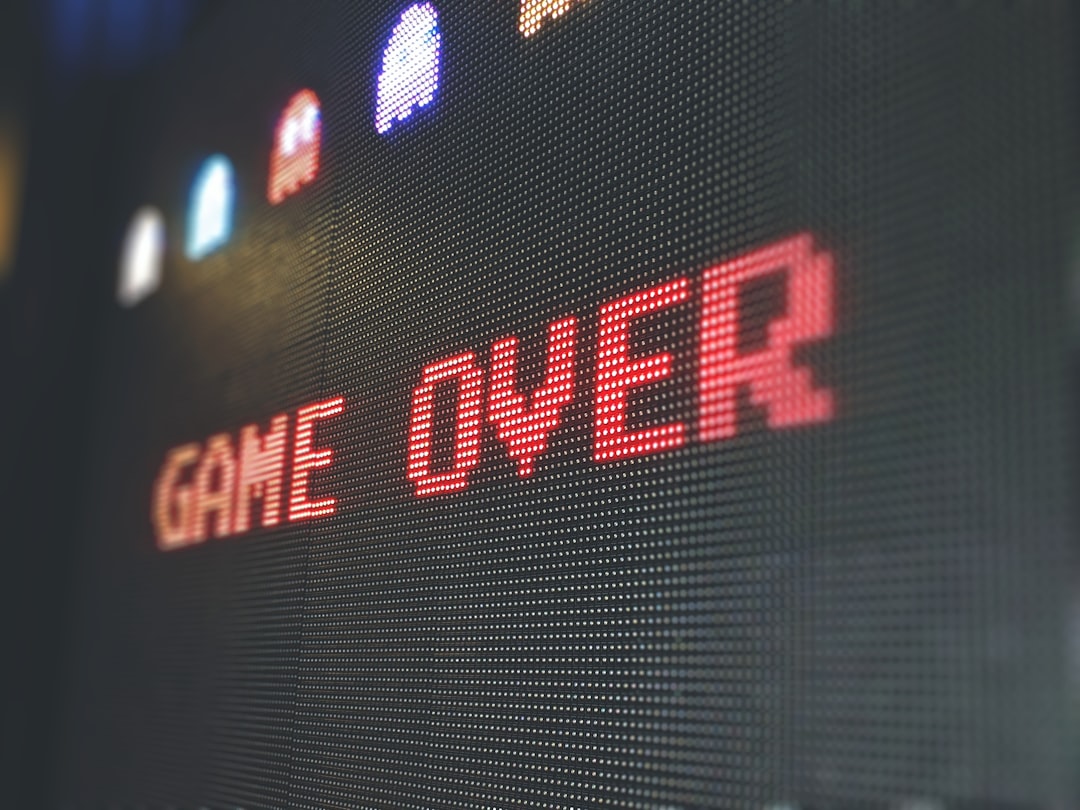

Gaming has always struck me as being like that. Primarily a drip feed thing: repetitive, hypnotic, addictive. It’s for the junkies with the itchy trigger finger. Keep scrolling for likes, keep shooting the zombies. The only computer game that ever kept me engaged was Kings Quest VI when I was nine, an adventure quest the precise details of which escape me now but I remember there was a labyrinth and a minotaur and a boatman across the River Styx and riddles to be solved. I played it for hours and hours in 1994 on a grey desktop monitor with dial-up internet. [Side note: I recently learned that it now enjoys cult status among gamers].

Anyway, apart from King’s Quest, there was nothing. I remember cruising totally uninterested past the early days of Mario Bros. Arresting TV commercials that ended with “Sega!” are all that really stick in the mind.

So, with the greatest will in the world, I concluded gaming is just not my thing. And while I appreciate that things have moved on considerably since 1994, I’ve never yet been tempted to reconsider my assessment.

Until now.

This is why.